Say you’ve inherited a rare genetic mutation that guarantees you’ll get a certain form of cancer by the time you reach 50 years of age.

And that this is most likely how you are going to die. But what if I told you this cancer gene, passed down from generation to generation, can be snipped out of your genome entirely and you never pass it on to any of your offspring?

That is the promise of CRISPR, which not only has the potential to radically change the genetic code of all of humanity but could also fundamentally affect our health care, food system, farming and even the manufacturing and production industries.

So WTF is CRISPR?

In short, it’s the technological discovery of the century. CRISPR (pronounced crisper) stands for clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats. And it’s a sort of immunity system set up in your genetic code.

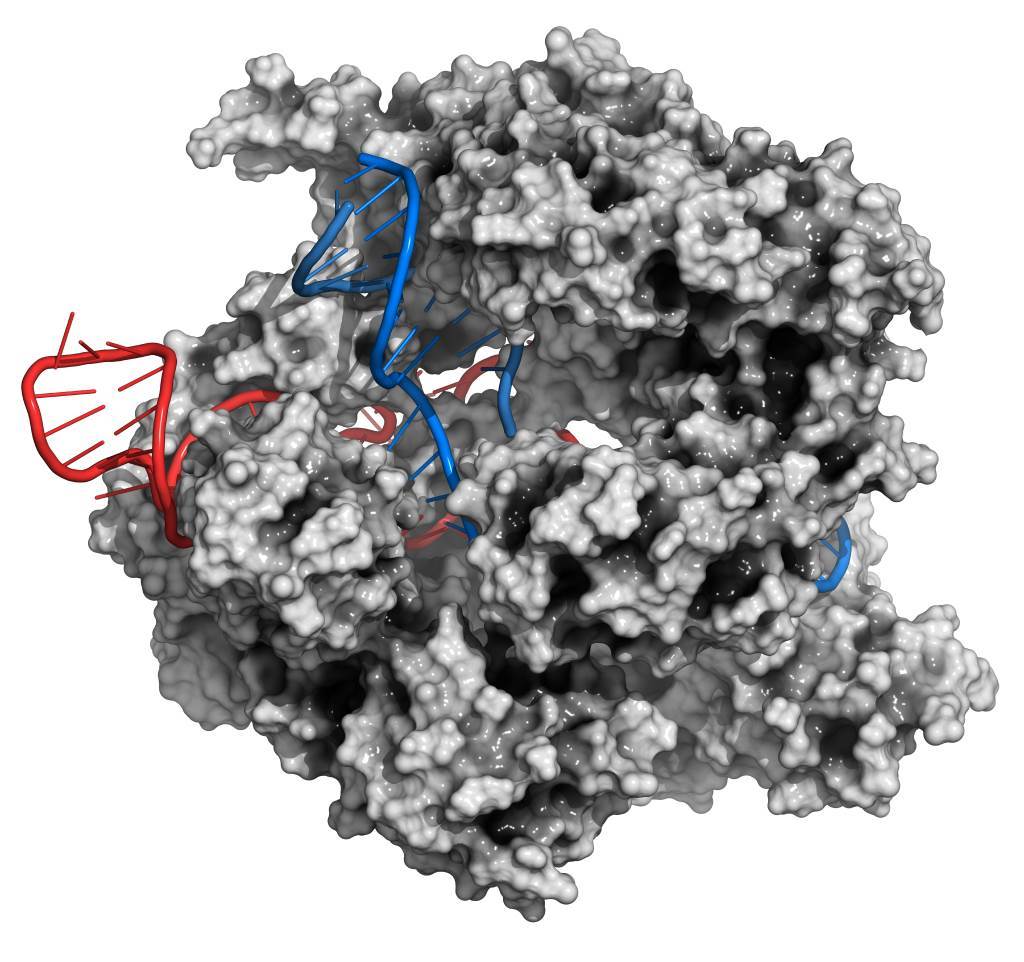

Our genes repeat in short sequences at certain intervals, and when our immune system detects a foreign gene — say a virus trying to insert its DNA into your DNA sequence — it creates a spacer between these repeats to provide immunity from that virus. This system, called CRISPR-Cas, can target and snip out undesirable code out at the spacers using a certain enzyme.

Cas9 was the first enzyme to be discovered within the CRISPR-Cas system and acts as a type of genetic scissors, allowing scientists to snip out, edit and replace DNA at certain intervals along the genome.

There is a bit of a trick to it, and the Cas9 enzyme needs some help guiding it to the right spot to do its job. Cas9 is able to make a precision cut using a small piece of pre-designed RNA (ribonucleic acid) sequence called guideRNA (gRNA). The gRNA essentially “programs” the Cas9 enzyme by binding to the DNA and then allowing the RNA sequence to lead the enzyme to the exact place you want to cut or add DNA.

CRISPR-CAS9 gene editing complex from Streptococcus pyogenes. The Cas9 nuclease protein uses a guide RNA sequence to cut DNA at a complementary site.

History decoded

If you think it’s tricky to snip out entire genes and hope for the best, just take a look at how we got here. Untangling who contributed what to the technology first is where things get really hairy.

CRISPR itself came on the scene well over a decade ago, but there’s now an ongoing battle among two major parties involved in the discovery and use of CRISPR Cas9. On one side is Berkeley’s Jennifer Doudna and her colleague Emmanuelle Charpentier who is now at Berlin’s Max Planck Institute. On the other side is Feng Zheng and his colleagues at MIT, who hold the majority of the patents for the technology.

Latest Crunch Report

All three have been up for a Nobel prize for their contributions to the work and all three have started and gone public with their own biotech companies using CRISPR Cas9 tech to create immunotherapies against cancer and other diseases. But who should own rights to the tech — potentially worth billions or even trillions of dollars — is up for debate.

Doudna and Charpentier published their work first in the journal Science and both shared a Breakthrough Prize recognizing their efforts in 2015. However, the main U.S. patent belongs to MIT. Though Doudna and her team filed first, MIT paid a fee to fast-track their patent submission — locking possibly the biggest discovery of our time in a war among two major contenders with backing from deep-rooted institutions and their own biotech firms.

Though Doudna and her team filed first, MIT paid a fee to fast-track their patent submission — locking possibly the biggest discovery of our time in a war among two major contenders with backing from deep-rooted institutions and their own biotech firms.

The legal battle wages on — and likely won’t be over anytime soon — but has so far cost each side tens of millions of dollars in lawyer fees.

With great power comes great responsibility

Like many scientific breakthroughs, this one comes with a lot of giant ethical questions.

For one, there are a lot of risks involved. With all the promise CRISPR holds, it’s not a perfect system, and scientists still need to do a lot more research here before we go messing with the human germline.

“With great power comes great responsibility,” says the ultimate genetically modified fictional human Peter Parker (aka SpiderMan). But you can only hold the world back so long now that the tech is out there and Chinese scientists have already started to inject human beings with modified cells in a trial study using the CRISPR-Cas9 technology.

Of course, this is a trial using cancer patients who haven’t been cured using other methods such as chemotherapy and may have no other options. And a similar trial is slated to start in the United States by the end of the year, pending approval from the federal Food and Drug Administration.

But how far do we take this technology? One could argue it’s okay to switch out genes causing debilitating diseases like cancer but what if we wanted to change our eye color or make our children stronger and taller? Is it okay to mess with the basic code of life just to keep up with some predetermined societal standard of genetic perfection?

We could be setting ourselves up for some dystopian future world where the rich can purchase a switch to more desirable genes, impacting all subsequent generations and further separating the perfect gene haves and have-nots or people splice in genes from other animals, potentially creating dozens of entirely new species of humanoids.

This could get weird, but given the rope, there are those who will go there. Plastic surgery is evidence of that.

But we’re not talking about a one-off job on one human. Editing our genetic code has repercussions for our offspring and their offspring who mate with humans who have not elected to do anything with their own genes. This is a decision that affects the whole of humanity and that will need some regulation.

CRISPR currently creates a loophole for at least the food system. The FDA says it won’t oversee scientists who clip out undesirable genes that, say, cause mushrooms to brown, because, unlike traditional genetically modified food, you aren’t adding in DNA from other organisms but simply taking something out. So it’s cool.

But the technology faces intense scrutiny from regulators when it comes to manipulating human DNA. The fear is we’re playing God with our own genes. But we’ve been doing that for a while, actually. This is just a new, more promising technique that needs further study.

The FDA, the Institutional Review Boards (IRB) and possibly the National Institute of Health (NIH) will be involved in determining approval for the first human study in the United States. Some argue this is duplicative and just more government over-regulation, while others don’t think we can tread carefully enough in what could potentially wipe out all inherited diseases in the future and radically change the human race.

Either way, we can only hold back the tide so long, and CRISPR will be changing our code, for better or worse, in the not too distant future.

![[Video] Reimagined for Orchestra, ‘Over the Horizon 2026’](https://loginby.com/itnews/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/Video-Reimagined-for-Orchestra-‘Over-the-Horizon-2026’-100x75.jpg)