Beginning today, a select group of Pittsburgh Uber users will get a surprise the next time they request a pickup: the option to ride in a self driving car.

The announcement comes a year-and-a-half after Uber hired dozens of researchers from Carnegie Mellon University’s robotics center to develop the technology.

Uber gave a few members of the press a sneak peek Tuesday when a fleet of 14 Ford Fusions equipped with radar, cameras and other sensing equipment pulled up to Uber’s Advanced Technologies Campus (ATC) northeast of downtown Pittsburgh.

During my 45-minute ride across the city, it became clear that this is not a bid at launching the first fully formed autonomous cars. Instead, this is a research exercise. Uber wants to learn and refine how self driving cars act in the real world. That includes how the cars react to passengers — and how passengers react to them.

“How do drivers in cars next to us react to us? How do passengers who get into the backseat who are experiencing our hardware and software fully experience it for the first time, and what does that really mean?” said Raffi Krikorian, director of Uber ATC.

If they are anything like me, they will respond with fascination followed by boredom.

The experience

It began when an Uber employee handed me a phone so I could hail a ride from the company’s app. A minute later, a Ford Fusion rolled up. Uber engineers occupied the two front seats, so I took a spot behind the driver.

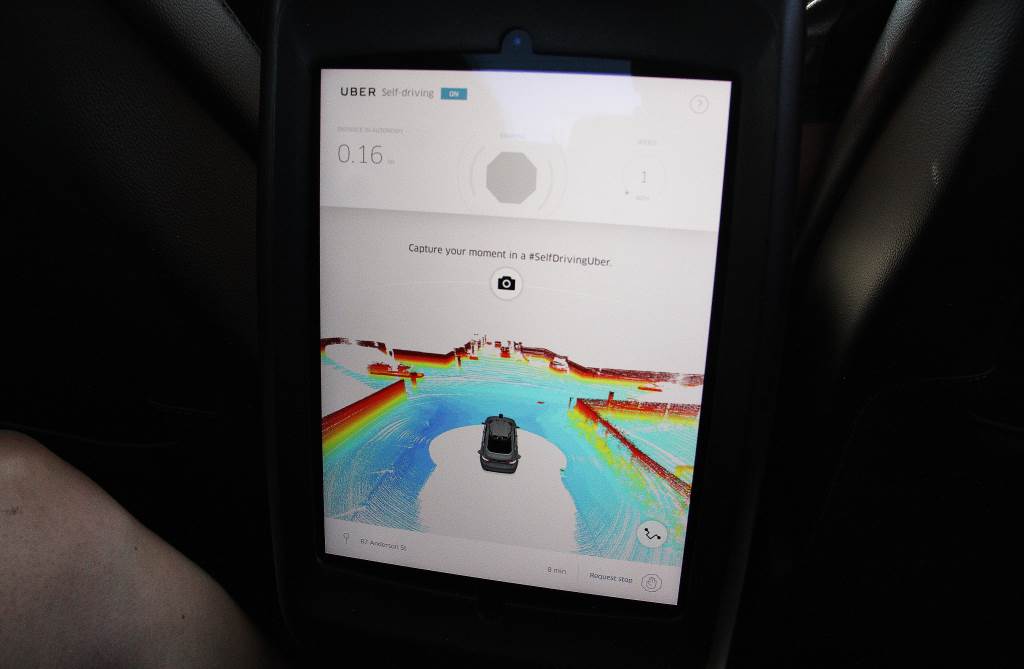

Once nestled into my seat, I selected a button on a tablet positioned in the back of the car to signal I was ready to go. The tablet displayed a live view of the car’s vision: blue for the road, red for objects. Our driving path took us from the ATC building in Pittsburgh’s Lawrenceville neighborhood through downtown and over the 9th Street bridge to the North Shore. The steering wheel turned on its own, as if possessed by a ghost.

The engineer in the driver’s seat spent the entire ride watching the road. He hovered his hands over the wheel and foot over the pedal. Whenever a stopped vehicle blocked an entire lane, he toggled back into manual mode to switch lanes and drive around — an action Uber’s self driving cars will not yet take. The second engineer sat in the passenger’s seat with a laptop open. On a normal trip, he would have been taking notes about the ride.

I had a flurry of butterflies the first time the car encountered an obstacle — an SUV backing into the road. You don’t notice how many unexpected incidents occur during a routine drive until you ask a robot to take the wheel. While we were passing over the bridge–and self driving cars struggle to position themselves on bridges to begin with–we came upon a large truck parked in our lane. The driver manually swapped lanes, right as a city worker darted out from in front of the truck and a banner dropped down near the front of our car.

You don’t notice how many unexpected incidents occur during a routine drive until you ask a robot to take the wheel.

I don’t know how the car would have reacted to the man or banner had it been in autonomous mode, but there were plenty of other instances to see it respond to its surroundings. It stopped behind a bus making a pickup, and again when the bus turned right. It read traffic light colors and stopped for one yellow light, while driving through a different yellow light. It obeyed traffic laws. It was so normal it got a little bit boring. The butterflies disappeared quickly.

Then the engineers let me “drive” the car back to the Uber campus. Once a light turned blue on the dash, I could hit a silver button in the center console to go autonomous. Braking, accelerating or hitting a red button brought driving back under my control. I took over once to maneuver around a stopped van.

It’s an unusual balance to focus on your surroundings while not having to do anything. It’s tempting to feel at ease and think about something else — maybe even drop your hands into your lap. I can see why the area between autonomous stopping and parking and fully autonomous riding is fuzzy.

I swapped seats with one of the engineers again and we took another loop around the city, this time through Pittsburgh’s busy Strip District. The road was cramped with parked cars. Vans stopped and started as they made deliveries at the markets and restaurants lining the road. It nudged slightly to the left when it noticed a parked car jutting out a bit too far, but otherwise rolled confidently down the street. A white SUV didn’t seem to mind finding itself sandwiched between us and another self-driving car, identifiable by its distinctive Lidar unit spinning on its roof.

Later, we sat in traffic on yet another bridge. The car started and stopped as we crawled forward a few feet at a time. Sometimes it was gentle, sometimes it came to a lurching halt. It felt a lot like riding in a car with a human driver, right down to the Uber map telling us we had reached our destination.

Planning for the unexpected

The autonomous Volvos that Uber is now dispatching to riders appear to be, for the most part, regular cars. The most noticeable difference is an array of sensors that jut out of their roof. Additional sensors are integrated into the cars’ sides.

A Lidar unit uses a laser to collect 1.4 million map points a second, resulting in a 360 degree image of the car’s surroundings. Cameras and a GPS system add additional intelligence.

I came away from my ride trusting the technology. The self-driving car detected obstacles, people and even potholes, and responded intelligently. The expected is already mundane. The bigger challenge for Uber is planning for the unexpected.

Uber is first offering autonomous pickups in a few Pittsburgh neighborhoods. Within a few weeks, it will expand to the airport and a northern suburb. The slow rollout is because Uber pre-maps the roads its cars travel — a practice Carnegie Mellon University researcher Aaron Steinfeld, who is unaffiliated with Uber, assured me is totally normal. The cars receive pre-collected maps that include speed limits and other generally applicable information so they can focus on real-time detection of variables like pedestrians.

Uber logs each of its road tests and uses the data to tweak how the cars should respond in specific situations. For example, the cars know that when they arrive at a four-way stop they should drive on in order of when they arrived. But what happens when another car fails to respect that order? It knows it should stop if another car jumps the gun, but it should also know to go if another car takes too long.

Humans still abide by many social cues when they’re driving. They make eye contact with other drivers and can read the subtle body language of a jogger that says they are thinking about cutting across the street. Uber’s cars can predict the likelihood that a pedestrian is about to cross the road, but reading actual social cues is still just a goal.

The company plans to switch to one ride-along engineer within the next six months. Eventually, the final engineer could be replaced by a remote help center; when a car encounters a foreign situation, it contacts a human in the center for help. Uber is also researching how to prevent accidental gridlock situations and how cars should behave when there are many pedestrians in the street.

Pittsburgh’s open door

Uber came to Pittsburgh for its engineering talent. Carnegie Mellon is home to a famed robotics program that has produced members of autonomous vehicle teams all over the country.

The city was quick to offer its support, too. Mayor William Peduto is an Uber rider and said the city is open to innovative companies that can bring new services and jobs to the city.

“Pittsburgh and, in particular, Carnegie Mellon University have been leaders in autonomous vehicle research for decades and this is a logical next step,” Peduto said. “Under state law, automated vehicles are allowed on Pennsylvania streets as long as there is a licensed driver behind the wheel, as there will be in the Uber rollout.”

Even the Uber driver who brought us to the event seemed intrigued. She wondered if she might become a self-driving car handler during the testing phase.

A few Uber employees mentioned weather as another perk for testing in Pittsburgh. While Google’s cars cruising around Silicon Valley might only see the occasional rain, Pittsburgh has four seasons. It’s also an old city with an irregular grid, bridges and lots of potholes.

“We like to call Pittsburgh the double black diamond of driving,” ATC’s Krikorian said. “If we really can master driving in Pittsburgh, then we feel strongly that we have a good chance of being able to master it in most other cities around the world.”

A litmus test

At no point did Uber suggest the current technology found in its cars is ready to roll out to the masses. Like Google, Carnegie Mellon and many other labs developing self-driving technology, it is carefully logging hours and hours of road tests. Its team is slowly working its way through a long list of scenarios its cars should be prepared to respond to in the wild.

“No amount of simulation captures everything, and that’s why…