Anne Miller showed the world what a miracle drug looks like.

The 33-year old nurse had been sick for a month after suffering a miscarriage in 1942. Her temperature spiked to as high as 107 degrees as she lay dying from childbed fever, once a major killer of young women.

“By an incredible stroke of luck, her doctor gained access to one of the first tiny batches of penicillin, which was not even commercially available yet,” Dr. Martin Blaser writes in his book, “Missing Microbes: How the Overuse of Antibiotics Is Fueling Our Modern Plagues”.

“Her recovery began within hours. The fever broke, the delirium ended, she could eat, and within a month she had recovered. It was the scientific equivalent of a miracle.”

Blaser learned the details of Miller’s case during a 1992 symposium at Yale. What happened next gave him chills, he says.

“In the third row, a small-boned, elegant, elderly woman with short white hair stood up and, with bright eyes, looked out across the room. She was Anne Miller, then in her 80s, given 50 more years of life by the miracle of penicillin,” he recounts.

This is what doctors and patients alike have in mind when they think of antibiotics, says Blaser, a New York University microbiologist who chairs the Presidential Advisory Council on Combating Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria.

“We are running out of time.”

And while antibiotics can be miracle drugs, they’ve been abused and overused so much that they are often useless against bacteria that evolve much, much faster than humanity can invent new weapons.

On Wednesday, the United Nations General Assembly voted to take “a broad, coordinated approach” to go after antimicrobial resistance. “This is only the fourth time a health issue has been taken up by the U.N. General Assembly (the others were HIV, noncommunicable diseases, and Ebola),” the U.N. said.

Today, penicillin almost certainly would not help an Anne Miller. She’d at the least need an improved version of penicillin such as ampicillin, which has extra compounds added to counteract the tricks that bacteria have evolved to survive a round of antibiotic treatment.

Related: ‘Nightmare Bacteria’ Found in U.S.

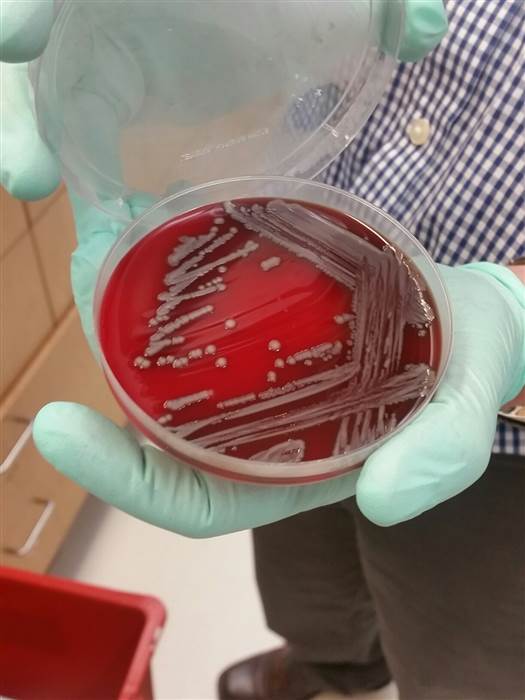

Drug-resistant “superbugs” are now found virtually everywhere. They’ve developed as people pop antibiotics to treat colds, the flu, ear infections and various other ills caused by viruses and fungi that are not affected by the drugs. They grow in farm animals fed antibiotics not to treat disease, but to make them grow fatter and faster.

They’re found in city sewer systems and in hospital sinks. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says in the U.S. alone, more than two million people are infected by drug-resistant germs each year, and 23,000 die of their infections. Globally, these antibiotic-resistant microbes kill 700,000 people a year.

The drug pipeline is not keeping up.

The last really new class of antibiotics was invented in 1984, according to the Pew Charitable Trusts. Every new antibiotic to hit the market since then – and there have not been many – is a variation on a decades-old design.

“If antibiotics were telephones, we would still be calling each other using clunky rotary dials and copper lines.”

“If antibiotics were telephones, we would still be calling each other using clunky rotary dials and copper lines,” says Stefano Bertuzzi, CEO of the American Society for Microbiology.

“Antimicrobial resistance poses a fundamental threat to human health, development and security,” Dr. Margaret Chan, director-general of the U.N.’ s World Health Organization, said Wednesday.

“We are running out of time,” she added.

Related: Inside the Lab Searching for the Next Superbug

The World Bank Group predicted this week that the economic damage wrought by antibiotic resistant infections will wipe between 1 percent and 3.8 percent off global domestic product by 2050.

“The scale and nature of this economic threat could wipe out hard-fought development gains and take us away from our goals of ending extreme poverty,” said World Bank president Jim Yong Kim. “We must urgently change course to avert this potential crisis.”

It’s not a new issue. Public health experts, infectious disease doctors, patients and advocates have all been warning about the problem for two decades. But antibiotic overuse persists, and the superbugs continue to pop up.

The most recent is the mcr-1 gene, found on a little clip of DNA called a plasmid that various species of bacteria can pass around and share like an internet meme. It gives them resistance to a last-resort antibiotic called colistin.

Related: What’s so Super About Superbugs

The U.N. plans to lead a global effort to help countries fight the threat. While some are struggling just to provide clean water to their populations, others, like the United States, are fighting epidemics that reach into flagship hospitals and that don’t discriminate between rich and poor.

Vaccines can help, as can better hygiene, safe water and better use of antibiotics.

…