Whether it’s googling flu symptoms, tweeting about our moods, or refreshing weather apps, our everyday smartphone and social media use might seem frivolous. But it may just solve some of the world’s biggest problems.

Collectively we’re producing heaps of data that researchers can use to track disease outbreaks in real-time, predict earthquakes, and even prevent suicides.

Tweeting an Outbreak

“This flu is horrendous. Can’t breathe, can’t sleep or eat. Muscles ache, fever 102. Should have gotten the shot. Time for a movie marathon.”

That’s a hypothetical example of the kind of tweets Alessandro Vespignani and his colleagues at Northeastern University sift through, searching for signs of the latest outbreaks. His team recently presented a model they say tracks the spread of flu up to six weeks in advance of traditional forecasts in the United States, Italy, and Spain.

Related: Smartphones Are Changing the Human Race in Surprising Ways

Vespignani’s lab is just one group participating in the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) “Predict the Influenza Season Challenge,” which began in 2013. The CDC traditionally tracks the flu by looking at doctor visits and lab tests. But participants in this new challenge are combining that information with novel data sets, like social media posts, Google searches, and Wikipedia page visits.

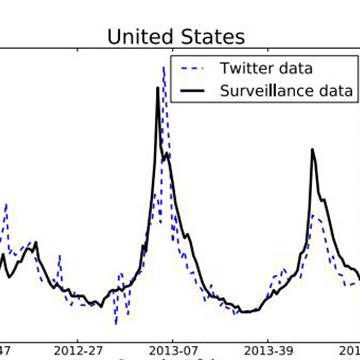

The idea is simple: Lab results take months, but tweeting is instant, says Michael Paul, a professor of information science at the University of Colorado, Boulder. Paul recently showed how Twitter could track the flu in real-time with reasonable accuracy in ten different countries. He says this could make a big difference in a places like South Africa, where flu statistics are only compiled months after the season ends.

Still, there are many challenges in trying to predict public health issues using social media. For one, there’s a lot of noise. It’s difficult to remove angry and ironic tweets from the data. It’s also difficult to know if mentions really translate to a larger population. Older people might be the most likely affected by a flu outbreak, but they’re also the least likely to be on social media.

“Those people who report their symptoms could have different personalities and different demographics,” says Isaac Fung, an assistant professor of epidemiology at Georgia Southern University. Fung has moved away from looking for signals in social media prior to outbreaks. Instead, he’s looking for patterns in social media reactions during outbreaks of infectious diseases.

“There are multiple reasons why people talk about health conditions,” Fung says. “We need to understand this before we can truly discern the signal from the noise. The science is still largely exploratory.”

Patient Secrets

Understanding those social media reactions could be especially helpful for researchers trying to figure out what patients are doing outside the doctor’s office.

“During an outbreak of a disease like Ebola or Zika, we have a pretty accurate picture of how many people are infected and where, based on hospital visits and lab tests,” Paul says. “But there are other pieces of the big picture that health officials need to know. There’s not an easy way to know how people are reacting to the outbreak, like if they are protecting themselves and complying with advisories. Social media can help fill in those holes in our knowledge, based on the reactions people share online.”

By analyzing social media, researchers could catch nascent health trends more quickly than through traditional surveys. For example, researchers at NYU Langone Medical Center are using tweets about vaping to find out how this smoking alternative is being marketed and how the trend is spreading.

But despite researchers learning to harness this data for good, privacy issues are still bound to dominate the conversation.

Some researchers are especially concerned about privacy on social networking sites created to connect people with similar health conditions. Those sites have clear benefits for patients, doctors, and researchers. But they’re also producing large data sets that would be “immensely valuable to companies looking to market products, or, in the case of insurers or employers, deny a policy or a job,” said Jingquan Li, an associate Professor of computer information systems at Texas A&M University-San Antonio, in the Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association.

A Weather Station (and a Psychiatrist) in Your Pocket

Even if you don’t publicly share about #vaping or about what it’s like to live with a chronic condition, your everyday smartphone use might reveal more information than you intend.

For instance, many people use the WeatherSignal App because it boasts localized, crowdsourced forecasts. But some researchers like the app because it anonymously collects data from its tens of thousands of users that ties their GPS locations to local temperatures, changes in pressure, and more as it creates its live weather map. And the accelerometer that detects which way you’re holding your phone can even double as a seismograph to sense earthquakes.

“Social media can help fill in those holes in our knowledge, based on the reactions people share online.”

“No one has really predicted an earthquake yet,” says Colin Price, a professor of atmospheric sciences at Tel Aviv University. Researchers are divided on whether it’s even possible to predict earthquakes. Since they happen so suddenly, researchers don’t necessarily know where to put a cluster of sensors to help understand what’s happening before, during, and after seismic events.

But if millions of people have smartphones in their pockets, why not use them to benefit everyone? Price recently started scanning WeatherSignal data to see if he can find new information that could lead to better warning systems and save lives during disaster events like earthquakes and wildfires. NASA is working on a similar project that uses GPS data from phones and other devices to better estimate the hazard zone of an earthquake.

Our phones don’t just collect data on the external world. Companies like Mindstrong and Google’s Verily are using “digital phenotyping” to understand someone’s mental health through the way they use a phone. According to a report in Nature, these companies are building tools that could analyze word choice, typos, voice patterns, and physical movements. These factors could reveal signs of diseases like Alzheimer’s or even signs…