Amazon recently unveiled a new type of grocery store — one that doesn’t require cashiers at all. Called Amazon Go, the brick-and-mortar location uses sensors and gates to automatically identify what you bought, calculate your total and charge you for your purchases when you leave. It gets rids of pesky long lines in front of cashiers or self-checkout kiosks, but also more or less eradicates the need for checkout counters altogether.

While that’s exciting for loathers of long lines (like me), it also sounds like it could cause a decline in employment, just as automation wiped out millions of manufacturing jobs over the last couple of decades. The reason for the drastic decrease there has been fiercely debated; many argue that trade agreements like NAFTA have resulted in jobs lost to other countries, but data suggests that increased productivity is really to blame.

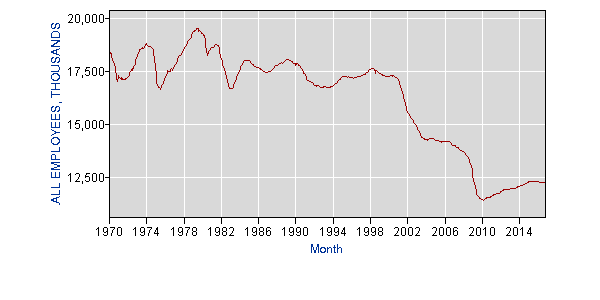

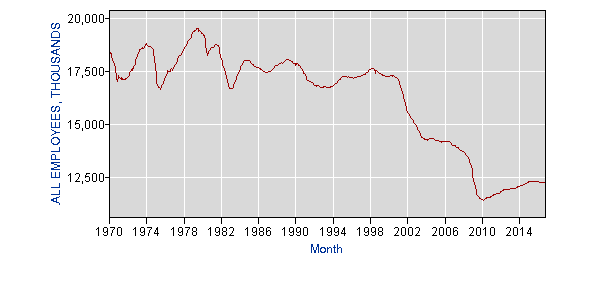

Increased productivity has traditionally been linked to improvements in technology, which enables more output without adding more workers. Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) shows that the number of jobs in manufacturing saw a sharp decline in 2000 (and then again in 2010 after the credit crunch), not 1994, when NAFTA went into effect. In fact, between the years 1994 and 1998, the number of employees hired in manufacturing actually increased, if only slightly.

According to a 2010 report by the conservative Heritage Foundation, which cites BLS data, declines in manufacturing jobs coincide with significant growth in productivity and output.

So it appears trade agreements are not to blame — increased productivity is the more likely culprit. And advances in technology are going to continue to impact employment. In fact, a World Economic Forum report from January of this year predicts that we will lose five million jobs by 2020, thanks to technology and automation.

What this, and Amazon’s new shopping tech, could mean for jobs in the retail sector, is unclear. While it’s easy to assume that this automated checkout system could replace human cashiers, many believe that existing staff could just be repurposed for other positions in stores.

Tom Coughlin, IEEE senior member and president of Coughlin Associates, believes that stores could get their employees to focus more on servicing customers by helping them locate items, and even assist them in bringing their heavy shopping out to their cars, instead of spending time trying to collect money from them.

Indeed, a report from the BLS also states that, in an effort to combat online shopping, brick-and-mortar stores may emphasize customer service to improve sales. “Traditional retail stores should hire more sales workers to provide this service,” according to the bureau’s retail industry forecast for 2014 to 2024, which projects a seven percent increase in jobs.

Human workers are also more versatile, and are able to perform a broad range of job duties that include helping customers find items, operating a cash register, and re-stocking shelves. “Because retail sales workers have this versatile range of functions, their usage should also increase,” states the report. It’s important to note, though, that most stores today already employ stockers and customer service attendants, so it’s not clear if companies will increase hires in those areas enough to compensate.

Of course, a lot of this is speculation sparked by Amazon’s introduction of its new retail format, which is only in one outlet in Seattle right now. Whether it will gain popularity and become more widespread is still unclear.

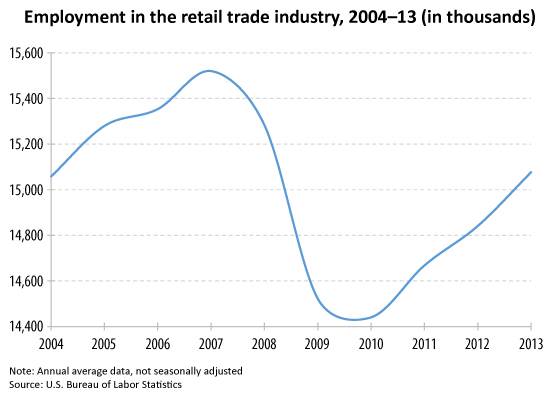

Even if this cashier-free system takes off, though, there are ways to maintain the number of jobs in retail. The rise of online shopping did not appear to severely impact the number of jobs in the industry between the years 2004 and 2013, although employment did suffer between 2007 and 2010 because of the overall economic downturn.

“A technology driven increase in productivity should not cost any net jobs,” said Josh Bivens, director of research and policy at the Economic Policy Institute. “The faster productivity growth we’ve ever seen came between 1945-1970 and 1995-2001 – and job-growth in these periods was the fastest, not slowest, on record,” he said.

Bivens believes that managing the macroeconomy to ensure enough growth in demand to soak up the extra productive capacity is key to maintaining the number of jobs. Of course, that’s easier said than done, and requires the injection of more money into the economy. And that means more than just increasing GDP, it means growing a base of consumers through increasing wages and creating new jobs. And those jobs can’t be focused entirely in high-skilled fields.

Regardless of the feasibility though, Bivens reiterated that technological advancements are not to be shunned. “But, the policy bungling is what’s to be feared, not the productivity growth,” he said. In other words, while it is possible that developments in tech, such as Amazon Go, and the resulting bump in productivity could kill jobs, it’s up to economists and politicians to make sure that it doesn’t.