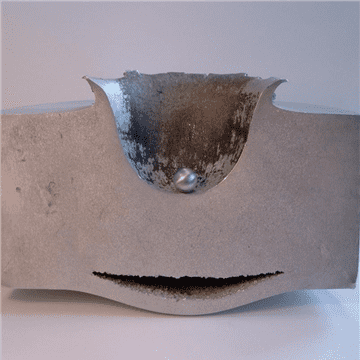

Retired NASA scientist Don Kessler found himself in an all-too-familiar role at last month’s European Conference on Space Debris: warning of an environmental crisis unfolding above our heads. Six decades of rocket launches have left behind a vast trash heap in orbit around Earth. There are now some 750,000 objects larger than a half-inch, all whipping around the planet at about 20,000 mph. At that speed, the impact of a small nut or bolt carries the wallop of a hand grenade. Even a pinhead-size chip of paint (there may be 100 million such bits up there) hits like a 22-caliber bullet.

For any satellite or astronaut working in space, it’s a serious problem.

But it’s still not the whole problem, as Kessler keeps reminding people. In a now-famous 1978 paper, drawing on his research at NASA’s Johnson Space Center, he and his colleague Burton Cour-Palais showed that collisions between pieces of debris in orbit could create more debris, leading to a potential chain reaction. If the amount of junk multiplies exponentially, that effectively turns all of low-Earth orbit into a no-fly zone — a worst-case scenario known as Kessler Syndrome.

Already, the International Space Station (ISS) bears numerous scars from impacts. In 2009, a dead Russian military satellite shattered a $50 million Iridium satellite, and near-misses are increasingly common.

Related: NASA’s Bold Plan to Save Earth From Killer Asteroids

When Kessler arrived at the space-debris conference, though, he had an unsettling sense of déjà vu. “There’s an awful lot of repetition going on, and it looks to me like there’s not a lot of progress that’s been made in the past 20 years,” he says.

Part of the solution, everyone agrees, is pragmatic: We need to control how much junk we send up. “We require a coordinated global solution to a global problem,” Brigitte Zypries, Germany’s minister for economic affairs, told those at the ESA conference. Releasing rocket stages at low altitudes so they quickly burn up would help a lot. So would forcing companies to make sure all fuel is vented from rockets or deactivated satellites that remain in orbit. Exploding fuel is a major source of space shrapnel.

At the conference, Hugh Lewis of the University of Southampton pushed for a rule that would require new satellites to return to Earth within five years after deactivation. Even without intervention, objects orbiting fewer than 500 miles above the ground will come down within a few decades due to drag from the uppermost wisps of atmosphere.

Waiting for the atmosphere to clean up our mess is not going to be enough, however. Computer models show there’s already enough junk in orbit to push us unnervingly close to the Kessler Syndrome.

“There are many different ways we could remove or remediate objects,” says space debris expert Thomas Schildknecht from the University of Bern. “But we need action. We need to go forward — now.”

In other words, we need to find a way to take out the space trash. And this is the point at which mild-mannered space junk experts improbably morph into techno-visionaries.

Snatch and Grab in Space

Almost every serious junk-removal concept under consideration sounds like something dreamed up by Tony Stark: electromagnetic lassos, gripping arms, solar sails, and laser cannons. That’s no coincidence. The technologies needed to remove pieces of debris from Earth’s orbit really are the same ones that inspired many science-fiction worlds.

“There are many different ways we could remove or remediate objects. But we need action. We need to go forward — now.”

First, take that electromagnetic lasso, technically known as a space tether. In January, the Japanese space agency, JAXA, attached a 2,300-foot-long spool of aluminum-and-steel cable to an uncrewed space station supply vehicle. Once unwound, the dangling cable would get enmeshed in Earth’s magnetic field and get pulled slightly toward the ground. In the future, dedicated satellites could approach large pieces of debris, latch onto them, wind out a similar cable, and drag the offending piece of junk to a fiery burn up in the atmosphere.

The space tether is also a core technology needed to build a space elevator, a high-frontier concept for a 22,300-mile-high lift that would bring objects from Earth into space without a rocket. Arthur C. Clarke popularized the idea in his 1978 novel “The Fountains of Paradise,” in which he explained it as “a tower, rising clear through the atmosphere, and far, far beyond.” JAXA’s low-budget tether test failed but more experiments will follow, each providing a back-door test of that elevated idea.

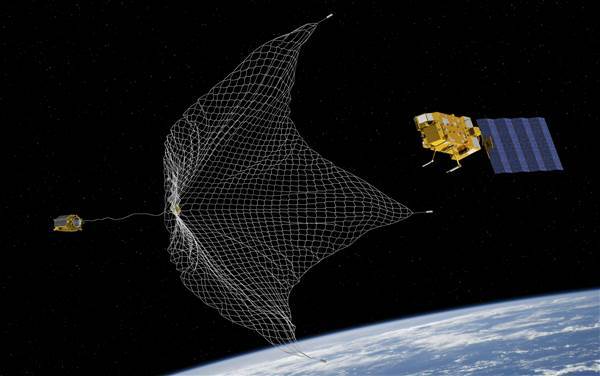

In 2021, the ESA plans to launch the first dedicated space junk removal mission, called e.Deorbit. It will hunt down a derelict satellite, grab it with a robot gripper or a net, and then steer it out of orbit. Being able to rendezvous with and capture a satellite is also just what you’d need to do if you wanted to lasso a small asteroid, clamp onto it, and start a space mining operation — extracting its water for fuel or its metals for construction materials.

A Mountain View, Calif. startup called Deep Space Industries is developing those technologies for a test mission called Prospector X, with funding and technical support from both NASA and ESA. The tiny nation of Luxembourg is also investing 200 million euros in asteroid mining, attracting attention from both Deep Space Industries and its rival, Planetary Resources, co-founded by Google’s Larry Page.

Related: Is This is the Key to Finding Alien Life?

An especially appealing way to pull a satellite out of orbit is with a light sail, which uses the sun’s energy to move an object and so needs no onboard propellant. Such a sail could push a space probe through the solar system just as easily as it could de-orbit a dead satellite; there’s no inherent difference between a space-junk sail and a space-exploration sail.

England’s Surrey Space Center is partnering with the ESA to create a “Gossamer Sail for Satellite Deorbiting.” Estonia plans a 2019 test of a related technology called an electric solar wind sail. In the U.S., the non-profit Planetary Society will launch LightSail-2 by the end of this year, with the aim of inspiring sail-powered vessels to tour the solar system.

“You could have very low-cost missions, universities sending spacecraft to the moon or asteroids powered only by the sun,” says Bill Nye, the Planetary Society’s CEO and well-known on television as the Science Guy. “What’s not to love?”

…

![[Interview] [Galaxy Unpacked 2026] Maggie Kang on Making](https://loginby.com/itnews/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/Interview-Galaxy-Unpacked-2026-Maggie-Kang-on-Making-100x75.jpg)