Researchers have invented a new type of artificial bone that can be shaped using a 3-D printer for customized implants.

The new material, which they call hyper-elastic bone, appears to act like natural bone in the body and can repair deformed bones and some injuries, the team reports in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

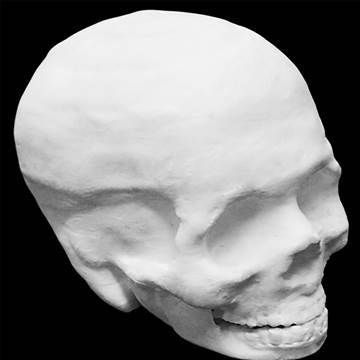

When the material was tested in a monkey, the bone fused to the animal’s skull, and new blood vessels grew into it, the team at Northwestern University said.

“Within four weeks, the implant had fully integrated, fully vascularized with the monkey’s own skull. And there is actually evidence of new bone formation,” Adam Jakus, a postdoctoral fellow in the department of materials science and engineering at Northwestern, told reporters in a telephone briefing.

Related: Scientists Print Living Body Parts

They hope to gain permission to test the implants in people within the next five years.

The material is cheap and appears to be useful for a range of bone injuries, including for the spine, skull and jaw, they said.

“The first time that we actually 3-D printed this material, we were very surprised to find that when we squeezed or deformed it, it bounced right back to its original shape.”

Currently, the best option is a bone graft from the patient, which can be painful and which doesn’t always work well, or donated bone from someone who has died. These transplants often do not heal well. Artificial bone grafts currently in development are often brittle and risk being rejected, also.

Jakus and assistant professor Ramille Shah developed a mixture of materials including hydroxyapatite, the main mineral component of natural bone tissue, which also lends itself to ink-jet printing.

Related: Regenerative Medicine Means Lab-Grown Body Parts

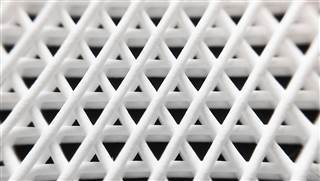

“Despite the fact that it is majority ceramic, which is usually very brittle, it possesses very unique nano and micro-structural properties that makes it highly elastic,” Shah said.

“The first time that we actually 3-D printed this material, we were very surprised to find that when we squeezed or deformed it, it bounced right back to its original shape.”

It can be “easily cut, rolled, folded, and sutured to tissue. And since it is elastic, it can be pressed, fit into a defect, and expand to mechanically fix itself into a space without glue or sutures,” she added.

“Since it is elastic, it can be pressed, fit into a defect, and expand to mechanically fix itself into a space without glue or sutures.”

They stuck some under the skin of a mouse and it acted like natural tissue. Cells grew on it and blood vessels made their way into it, much like natural bone.

When they put some into a soup with immature human stem cells pre-programmed to form bone or muscle, the cells took right to the new material. “One of the truly astonishing things that happened was that the stem cells actually turn into osteoblasts, or bone-like cells over the course of this time. And this was just because of the material,” Jakus said.

The material could be used for tailor-made implants, perhaps based on MRI and other scans. And various sizes and shapes of bone could be pre-printed for wider use, because the material is easy to cut and shape more precisely later on.

“So this makes it really ideal for those third-world applications where you could just ship it way ahead of time, have it on the shelf until it’s needed rather than having to create a complex biomaterial that needs to be heavily refrigerated or frozen,” Jakus said.

“In most of these cases, like in third world countries, those types of facilities may not be accessible. So being able to open a package and to use the material is fantastic, both in the United States and first world nations, as well as third world nations.”