Have a friend who likes Donald Trump? The GOP presidential nominee may soon be trying to get to know you, too.

Amid a pricey last-minute scramble to build a fundraising and data infrastructure after spending much of his bid arguing he didn’t need such tools to win the presidency, Trump’s campaign has launched a new app that aggressively mines supporters’ data — and if they allow it, supporters’ friends’ data — in controversial ways privacy experts say are troubling.

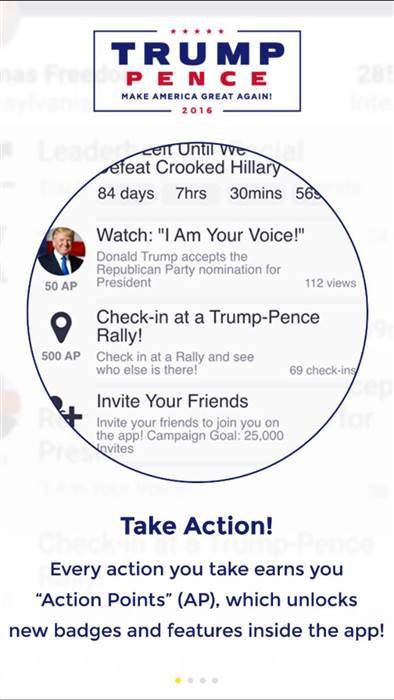

The app, America First, is part social network and part competition, gamifying the election: You get points the more you donate, share the app, and support the candidate. Watch an ad? Collect 50 points. Check in at a rally? Rack up 500 points.

Four days after its official launch late last Friday, there are already 29,000 accounts — with users’ names shown to all other users — on the leader board. An account purporting to be House Speaker Paul Ryan’s former primary challenger Paul Nehlan ranks at No. 2 nationwide, with 170,235 points garnered through the application.

But along the way, Trump’s app can capture and use a huge amount of personal data — something privacy experts warn is invasive.

Related: How Trump Spent $8.4 Million to Play Digital Catch-up

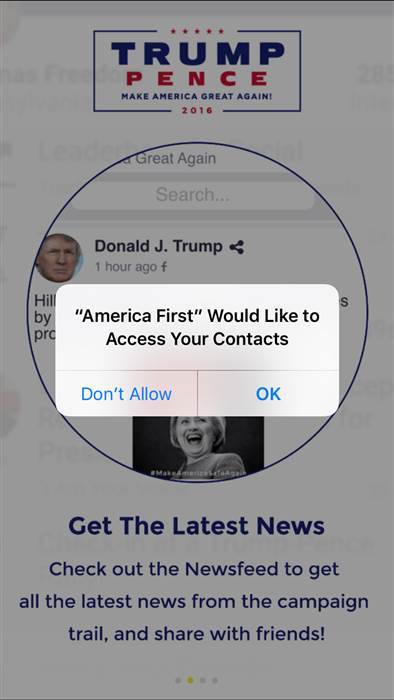

Immediately after installation, the app requests access to users’ address books; app creator Thomas Peters, CEO of uCampaign, said this is to help users’ share the app with their friends. But the app’s privacy policy says the campaign can use that data — the names, emails, home addresses and more stored in a user’s address book — however they’d like.

“Trump’s [app] is at a whole other level,” explained the American Civil Liberties’ Nicole Ozer. “It’s not just to pay with your privacy, but to sell out your friends and colleagues who are in your contact list.”

To be sure, this doesn’t mean the Trump campaign is doing anything with users’ data — it just means it can. And some users may not know it: David Levine, an Elon University professor and affiliate scholar with Stanford’s Center for Internet and Society, said consumers don’t always read privacy policies. What’s more: Less than half of all Americans knew what a privacy policy was in a late 2014 Pew survey.

Trump’s request for immediate data access, without offering up more reasoning or limits, is “extremely troubling,” Levine said. While not unheard of, it’s controversial and “a question of ethical behavior.”

For Republican voters, the app may feel familiar: It’s almost identical to the app Trump’s former rival Ted Cruz commissioned for his primary bid. That app, also created by uCampaign, earned the Texas senator questions over similar privacy concerns. At the time, Cruz organizers said the users’ address book data could be tracked, but wasn’t being downloaded by the campaign.

Ozer, the technology and civil liberties director of the ACLU in California, reviewed for NBC News the privacy policies for both Trump’s app and that of Democratic rival Hillary Clinton. Clinton’s is more typical of how consumer apps request and use data, she said, while Trump’s privacy policy gives him enormous breadth across the board for how data is collected, used, and distributed — now or anytime in the future. It also goes as far as to disavow what might happen to data at the hands of third parties. (Clinton’s app says it will take “reasonable measures” to stop third parties from infringing on users’ privacy.)

Related: Where will the Republican Party go after 2016?

“We may access, collect, and store personal information about other people that is available to us through your contact list,” reads the Trump privacy policy, which also notes that it can change at any time without notifying users.

Peters said all data sharing is voluntary — with at least one question of consent on the app — and users’ friends won’t be contacted unless their friends initiate contact through the app. He said the campaign is likely to use the data when trying to target a specific group of voters, by looking for app users who already know that voter and encouraging them to reach out to them on behalf of the campaign. So if the campaign is looking to boost its Ohio supporters, for example, they might ask a Trump fan in Illinois who is friends with a slew of Ohio Republicans to encourage his friends to support Trump.

“It’s a really fun feature, the way lawyers describe it is really scary,” Peters said. But he couldn’t explain why the privacy policy offered up such wide latitude for using data if that wasn’t its intent, instead directing NBC News to the Trump campaign and its lawyers, who did not answer interview requests.

“Fundamentally, you have one person deciding to use the app,” Ozer said. “All of this sensitive information of all these other people … is ending up with the Trump campaign if that individual clicks ‘I agree.'”