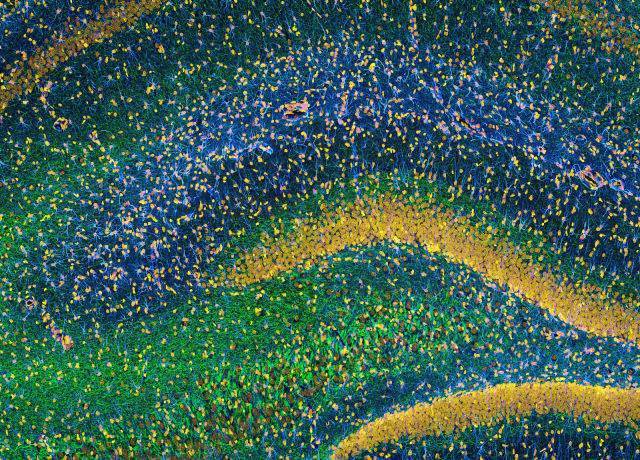

The rat hippocampus. (credit: National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research)

Memories allow us to record and store information, a central feature of our lives. Since the groundbreaking case of HM, a patient who lost the majority his hippocampus, we’ve known that this brain structure is central to forming long-term episodic memories. But we’re still unsure about how the neurons of the hippocampus change at the cellular level to lock those memories in place. A new paper published in Science provides a new insight on this: two different types of neurons, with different activity and adaptability, are both needed to handle memories.

The researchers behind the new study tracked the neural firing patterns of rats that were placed in mazes and allowed to find their way out. The authors were most interested in examining a type of neuron known as a “place cell.” These place cells are hippocampal neurons that are activated when the rat finds itself in a particular place—they play a role in orienting the animal to its environment. Critically, these cells are central to recalling memories—both positive and negative—associated with a location.

The researchers studied these neurons in rats that navigated around a maze, and as they took a post-maze nap to allow them to consolidate their new memories. The authors were interested in a phenomenon called sleep-related hippocampal sharp wave ripples among these rats.

Read 7 remaining paragraphs | Comments

![]()

![[CES 2026] A Care Companion for Family Health and Safety –](https://loginby.com/itnews/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/1768059032_CES-2026-A-Care-Companion-for-Family-Health-and-Safety-100x75.jpg)