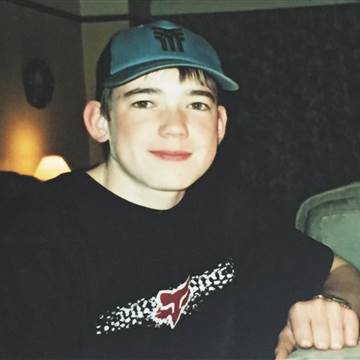

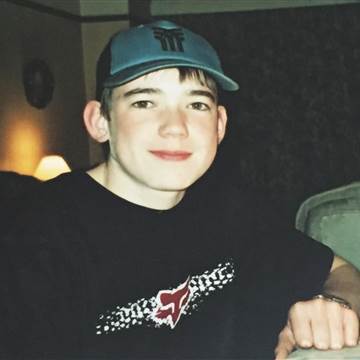

Before Thomas Evans was killed carrying out a terrorist attack for al Shabab in Kenya, he was radicalized in a red-roofed house in a small English village, right under the noses of his mother and brother.

“It was happening upstairs in our bedroom,” Sally Evans said. “He was on his computer.”

A year after she learned of her son’s death through pictures on the internet, Evans still wonders what could have prevented the 25-year-old’s descent into extremism.

More than 3,000 miles away, in a massive Manhattan office building, researchers at Google think they may have found an answer to that question.

Developers at Jigsaw, the tech giant’s think-tank, are two months into a pilot project called Redirect, which aims to push web users searching for jihadist information toward content designed to counter the slick tools of terrorist recruitment.

“There are people interested in ISIS’ message on one side and there are videos that undermine ISIS’ message on the other hand,” said Yasmin Green, head of research and development at Jigsaw. “We are using targeted advertising to marry the two.”

“I think what we’re seeing now is a recognition that tech companies have a moral obligation to not just stop their platforms being used for recruitment, but … to actively prevent the radicalization”

In traditional targeted advertising, a new mother searching for information on Google about getting a baby to sleep might start seeing ads for blankets and white-noise machines in their feeds.

Through Redirect, someone searching for details about life as an ISIS fighter might be offered links to independently produced videos that detail hardships and dangers instead of the stirring Madison Avenue-style propaganda the terror group puts online.

“So if you were looking for, let’s say, material on the social welfare system in the so-called caliphate, you would click on the ad and see the truth about what’s happening in Syria and Iraq,” Green said. “The long food lines, the devastated suffering, the failure of the Islamic State.”

Jigsaw invited NBC News into the lab where its counter-programming project is unfolding and revealed its preliminary results. In the first eight weeks, 300,000 people looking for ISIS information online were redirected.

They watched a combined total of 425,000 minutes of video, which Green said was a surprisingly high level of engagement given the short attention spans of internet users and the ability to just click away from anything dissonant.

The key is subtlety. A disaffected young person wondering if ISIS is the answer to their problems would immediately dismiss a video with a warning from the Department of Homeland Security. Instead, Jigsaw is looking for voices that will be seen as credible, such as imams, and a more measured tone.

“We really need to engage them with content that isn’t judgmental off the bat,” Green said.

Related: The Inside Story of an American ISIS Cell

Sohail Ahmad said he knows first-hand how effective this approach can be.

Raised by Pakistani immigrants in London’s East End, his family’s own hard-line views were reinforced by online videos and articles selling the idea that a global Muslim brotherhood could be achieved through jihad.

“It was through Google searches and it was through using YouTube,” Ahmad said.

He became a student preacher, spewing fanaticism and hate. He said he despised America and began seriously thinking about carrying out a lone-wolf bombing attack in London.

He never went through with it, and over time his views shifted. If Redirect had been in effect during his march toward extremism, he might not have gotten so far down the road, or turned back sooner.

“What led me away from radicalism was kind of listening to more relatively moderate scholars and imams,” he said. “And if I’d had access to that information, if I’d been exposed to that much earlier, I think I would have turned away from extremism at a much earlier stage as well.”

It’s no secret that technology has revolutionized terrorism. Militants bombard social media with posts meant to entice the curious and malcontented. Companies that run those sites play a high-stakes game of whack-a-mole trying to remove material and disable accounts that just spring up again.

“For recruiters who are based in conflict zones, they have a unique ability now to reach anybody, anywhere, at any time,” said Shiraz Maher, senior research fellow at the International Center for the Study of Radicalization at King’s College.

But Rashad Ali, a reformed radical who is now a senior fellow for the Institute of Strategic Dialogue, said tech companies have even more power.

“If you target your ads, we’ve found that you can go from reaching 500 people to 100,000 people in a matter of weeks,” he said. “I think the potential for reaching people who are vulnerable is huge.”

Ali said tests he has conducted show that targeted ads can reach subjects on a deeper level, too: A dozen members of a far-right organization reached out to the makers of one counter-programming video and asked for help leaving the movement.

“I’ve actually got no doubt that it can work,” he said.

“I think what we’re seeing now is a recognition that tech companies have a moral obligation to not just stop their platforms being used for recruitment, but where and when they can, to actively prevent the radicalization,” Ali added.

“As someone who’s been radicalized and been involved in recruiting other people, I think this is the least that Google can do.”

Google said it responds to requests for users’ data from government agencies and courts “on an individual basis.”

…