Now that I’ve wrapped up the major GDC product launches, I want to spend a bit of time talking about the rest of GDC.

The annual show has always been a big draw for game developers and hardware companies alike, and since the end of the Great Recession that process has only accelerated. But without a doubt the fastest growth in terms of developer and vendor presence at the show has been VR. GDC 2016’s VR sessions exceeded any and all expectations – the show management had to scramble to move them to larger spaces because the attendance was so high – and it took all of half a year for VR to become its own stand-alone show as well with the GDC spinoff VRDC. Suffice it to say, the amount of attention being paid and resources being invested in VR is very significant, both for software and hardware developers.

So for GDC 2017, I spent an afternoon on the expo floor dedicated to VR meetings, to see what new hardware was on display. While a common theme throughout is that everyone is still looking for the killer app of VR – both in terms of hardware design and the actual must-have game/application – it’s clear that there’s a lot of progress being made for future VR headsets, and that developers aren’t afraid to experiment in the workshop and show off those experiments to the public.

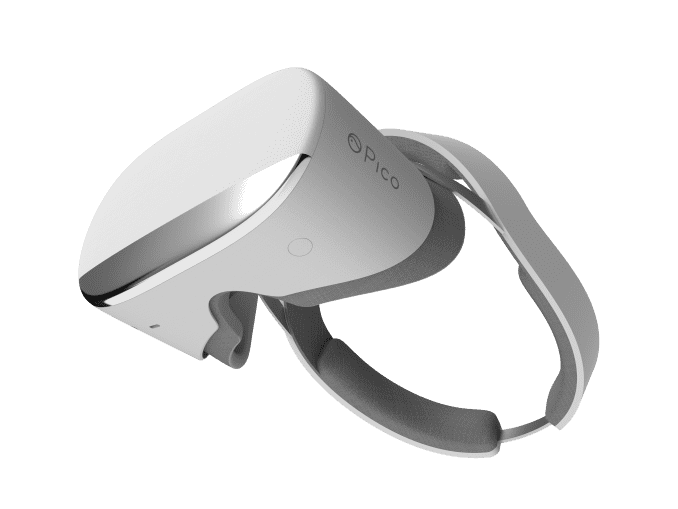

Pico Neo CV – Stand-alone VR Headset with Inside-Out Tracking

The first stop was Pico Interactive’s booth, where the company was showing off their Pico Neo CV headset. Pico is one of several companies developing headsets around Qualcomm’s Snapdragon SoCs, for whom VR has become a priority. Already a major force in high-end smartphones, Qualcomm believes that the Snapdragon is a great fit for VR given the mix of portability and high-performance required. As a result the company has gone all-in on VR, dedicating quite a bit of engineering and marketing resources towards helping their customers develop VR headsets and bring them to market.

Pico headset, in turn, is one of several headsets in development based around a Snapdragon processor. However more than just being a stand-alone headset for the purposes of on-board processing, arguably Pico’s big claim to fame in the world of VR development is their inside-out position tracking, which is designed to do one better than current VR headsets. Whereas setups like the Samsung Gear VR and various Cardboard headsets primarily rely on inertial tracking, the Pico Neo CV can do true inside-out tracking, fixing itself relative to the outside world on an absolute basis.

The advantage to positional tracking is that it allows much greater accuracy, which in turn allows for greater freedom of movement than inertial tracking. You can actually do a lot by interpolating accelerometer and gyroscope data from Inertial tracking, and as a result it’s generally satisfactory for rotation – think 360 degree videos and fixed-position gaming such as Gunjack – but it is ultimately limiting in what can be done with interactive experiences where errors add up. The drawback to absolute tracking is that it normally takes an external camera or beacon of some kind – such as the Vive Lighthouse system – which in the case of stand-alone, untethered headsets is antithetical to their portability.

The solution then, as several companies like Pico are playing with, is inside-out tracking. In the case of the Pico Neo CV, the company combines the usual gyroscope and accelerometer data with a camera looking at the outside world, using computer vision processing to extract the user’s position relative to the rest of the world. Computer vision is a fairly straightforward solution to the problem – witness the number of self-driving cars and other projects using CV for similar purposes thanks to the explosion in deep learning – but it’s made all the more interesting on a headset given the processing requirements.

In the case of the Pico Neo CV, while the company won’t be shipping the headset until later this year, they already have a prototype up and running, inside-out tracking and all. In my hands-on time with the headset, the positioning of the Neo seemed very accurate; the demo software always reacted to my head position as I felt it should across all six degrees of freedom, and pulling off the headset to check my actual position revealed that I was positioned where (and facing where) I should be. It’s an experience that in principle is no different than using external tracking, but then that’s the point of inside-out tracking: it is meant to be the same thing, but without the external gear.

That said, like the first-generation of PC headsets, I suspect the Pico Neo CV is going to be a transitional product as the hardware further improves. The camera-based tracking system only updates at 20Hz, meaning there’s 50ms between position updates. Without getting deeper into the headset I’m not sure what the actual input lag is, but the low refresh rate is noticeable if you turn your head quickly. In my experience it’s not nauseating in any way, but like some of the other drawbacks of first-generation VR headsets, there’s clear room for improvement. The headset display itself operates at 90Hz, so it’s a matter of getting tracking operating at the same frequency.

Part of the catch, I suspect, is processing power. The Pico Neo CV is based around a Snapdragon 820 SoC, which although is powerful by SoC standards, now is splitting its time between rendering in VR and processing the additional tracking information. Future SoCs are going to go a long way towards helping with this problem.

Looking at the rest of the headset, Pico has clearly set out to develop something better than the vast array of cellphone-powered VR experiences out there. Pico has combined their tracking gear and the 820 with a pair of 1.5K displays, so the total pixel count – and resulting DPI – is a lot higher than on a Cardboard or Daydream setup. Along with built-in audio, and the Pico Neo CV is everything needed for stand-alone mobile-caliber VR gaming.

Pico hasn’t yet announced a precise launch date for the headset, but they expect to start selling it later this year. As one of the first serious efforts at a stand-alone Snapdragon-based headset, it should be interesting to see where these kinds of devices fall into the market, and just how much more Pico can improve the inside-out tracking before the headset’s launch.

Tobii – VR Eye Tracking

Going from the inside looking out, let’s talk about the inside looking even further inside. One of the technologies various companies have been investigating for second-generation VR headsets is eye tracking. Besides enabling a more immersive experience, eye tracking could also potentially change how VR rendering works by allowing foveated rendering. By using eye tracking to keep tabs on what direction a user is looking, foveated rendering would allow games to efficiently render in a non-uniform fashion, rendering at full quality only where a user is looking, and rendering at a lower level of quality outside of that focus area.

But to get there you first need to be able to accurately track users’ eyes, and that’s where Tobii comes in. The company, which focuses on eye tracking for gaming and other applications, has already made a name for itself with their eye-tracking cameras, which are available both stand-alone and integrated into some laptops and displays. The use of external eye tracking has proven a bit gimmicky, but the technology is sound, and VR stands to be a much more useful application.

To that end, the company was at GDC showcasing a modified HTC Vive headset with their eye tracking technology installed. The company’s demo was primarily focused on how eye tracking can improve the gaming experience, both as an input method and as a way to add life to avatars, and true to their claims, it worked. The eye tracking implementation in the company’s modified headset was very rapid, to the point that it didn’t feel like it was operating any slower than the headset tracking. And while it took some practice to get used to – it’s a bit jarring at first that where you look actively matters – once I got used to it, it worked very well.

[embedded content]

But from a technical perspective, perhaps the most impressive part was just how well the company had integrated the eye tracking hardware into the headset itself. While the external cameras were by no means big to begin with, I was surprised just how easily it fit into the prototype. Adding eye tracking did not make the headset feel significantly heavier, and the sensors easily fit into the already limited free space inside the headset. From a hardware perspective, this very much felt like a technology that was already at a point where it could get integrated into a commercial headset tomorrow.

Consequently, if Tobii’s technology (or similar eye tracking tech) shows up in second-generation VR headsets, I would not be the least-bit surprised. While I’m not sold on the gaming aspects of the tech – it’s neat, not must-have – it’s the kind of thing where I expect developers would need some time to play with it to really figure out if it’s useful and just what the best use cases are. Otherwise the big use case here is going to be foveated rendering, which is likely going to prove critical for higher resolution VR headsets. The latter is outside of Tobii’s hands, but offering a good eye tracking experience is the first and most important part in making that happen.

HTC Vive – Hand on with the Deluxe Audio Strap & Tracker

My final stop for the afternoon was HTC’s private demo room, where the company was showing off some new games and other software technology being developed for the Vive. We’re at least a year too early for second-generation headsets, so the company wasn’t showing off…