Far in the back of a twisty, narrow cave in South Africa lie the remains of three pre-humans with small heads and clever hands.

The discovery, and research done on a cave full of 15 skeletons nearby, strongly suggests the little hominids were much less ancient than previously thought. It also suggests that they may not only have lived alongside more modern humans, but buried their dead and, perhaps, made and used tools.

The hominids, called Homo naledi, had brains about a third the size of ours but had modern-looking hands and backbones. The first fossils were only found in 2013 and their discovery has caused heated debate ever since.

An international team of paleontologists has now dated the bones to between 226,000 and 335,000 years ago — a much younger age than other finds had predicted. And a second cave containing the remains of three more individuals strengthens the argument that the dead were put there on purpose, the teams of researchers report in the journal eLife.

Related: Did Homo Naledi Bury Their Dead?

The second cave is about 100 yards away from the first cave, the discovery of which led to debate about when Homo naledi lived and whether the pre-humans had deliberately buried their dead.

“This likely adds weight to the hypothesis that Homo naledi was using dark, remote places to cache its dead,” University of Wisconsin-Madison anthropologist John Hawks, who worked on the study, said in a statement.

“What are the odds of a second, almost identical occurrence happening by chance?”

The team used several different methods to date the ancient bones.

“This likely adds weight to the hypothesis that Homo naledi was using dark, remote places to cache its dead.”

“When we first identified the fossils, most of the paleo-anthropologists on site were convinced that they would be a million or two million years old, but we have now shown they are much more recent,” said Paul Dirks of James Cook University in Australia, who worked on the study.

“It means that a primitive hominid persisted on the landscape in Africa for a very substantial period of time, well beyond what paleo-anthropologists predicted to be possible.”

The earliest examples in the area of modern humans, Homo sapiens, date to around 200,000 years ago.

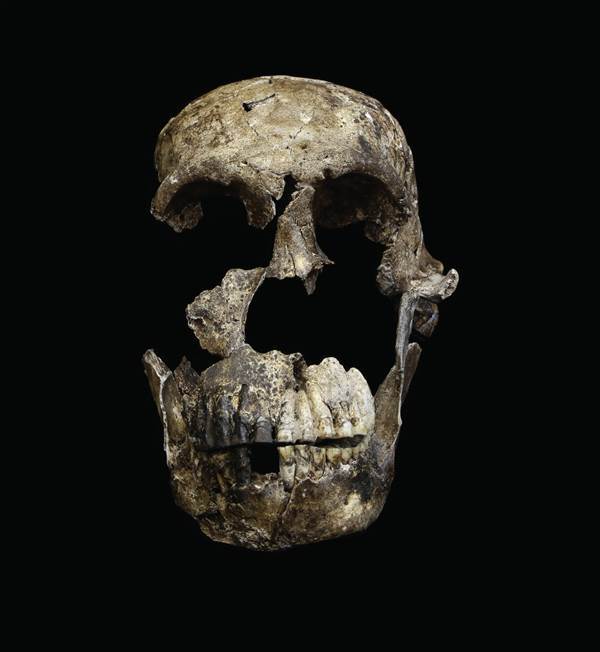

The three new skeletons come from two adults and a child about 5 years old, the researchers report in a series on studies published on the finds.

One of the adults has a very complete skull.

Related: Mastodon Discovery Could Upend Our Understanding of Early North America

“We finally get a look at the face of Homo naledi,” said paleontologist Peter Schmid of South Africa’s University of Witwatersrand, who pieced the skull together.

The adults would have stood around 5 feet tall and would have weighed around 100 pounds.

“What is so provocative about Homo naledi is that these are creatures with brains one third the size of ours,” Hawks added. “This is clearly not a human, yet it seems to share a very deep aspect of behavior that we recognize, an enduring care for other individuals that continues after their deaths. It awes me that we may be seeing the deepest roots of human cultural practices.”

Related: Fresh Fossils Could Force a Rewrite of Human Prehistory

The discovery will not end the debate about how the skeletons got into the caves. Some paleontologists doubt that such early humans were deliberately burying their dead.

“There’s a big debate, on whether it’s a burial ground or they were trapped there,” Dirks said.

“They could have been chased by lions or other humans, they could have got stuck in the cave. There are enormous storms in the region and there is evidence of meteorite impacts of a similar age in the area. You can speculate all you like, but at the moment the original hypothesis, that they were placed there on purpose, still holds.”

More and more studies are showing that the evolution of humans was messy and complicated. It was not just a steady progression from the primitive Australopithecus species best represented by Lucy to Homo erectus and then to more modern Neanderthals and fully modern humans. Instead, various species lived alongside each other and in some cases interbred.

![[MWC 2026] A Sound Immersion Experience With Galaxy Brings](https://loginby.com/itnews/wp-content/uploads/2026/03/1772736146_MWC-2026-A-Sound-Immersion-Experience-With-Galaxy-Brings-100x75.jpg)